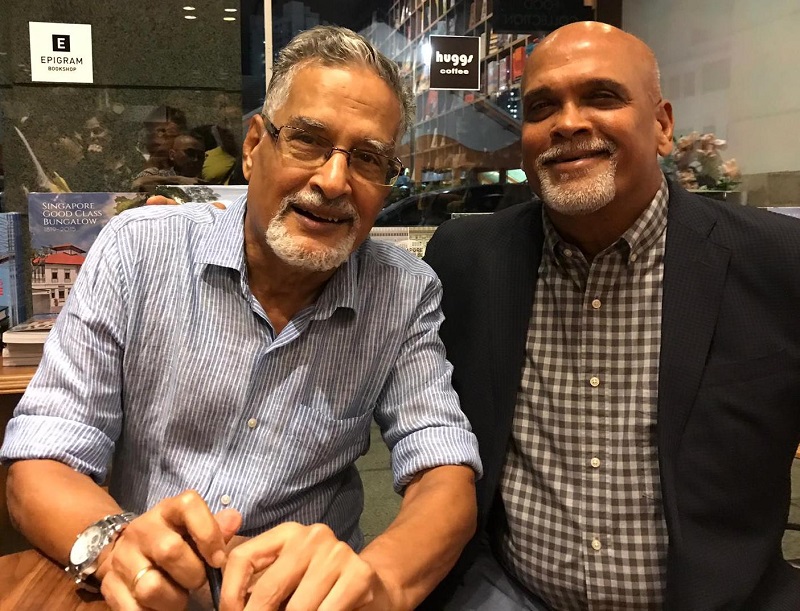

THIS is probably a rarest “first” in the world: Two bright brothers, one a leading newspaper editor of a terrific tabloid that cracked the news-stands with its flashy football coverage, and the younger, who was Singapore football coach in the early 1990s, when the Lions were at its morale-lowest and even relegated from the Malaysian League.

Same time, same place, same happenings. And how sibling considerations were simply put on the sidelines as they professionally carried out their respective duties without fear or favour. And even 27 years later, both unashamedly admit how they still harbour the enduring pains of accidental double-crossings.

Both probably had one of the longest Malayalee names, the editor, as Poravankara Narayanan Nair Balji and his only “bola-crazy” brother, Poravankara Narayanan Nair Sivaji, and they went by the short and sweet nickname of P.N. in professional circles.

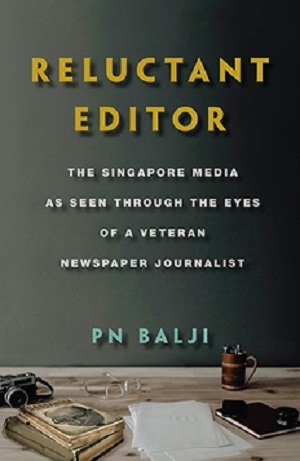

P.N. Balji last week formally launched his 10-chapter, 200-page breathtaking book, “The Reluctant Editor”, which recounted the highs and lows of his four-decade newspaper career and candidly confessed that he deliberately pulled out a crucial chapter which would’ve been: “How The New Paper (TNP) made Malaysia Cup a national past-time”.

At the height of the Malaysia Cup fever, from the late 1970s, with the “Kallang Roar” at its rousing regular 60,000-capacity at the now-defunct National Stadium, The New Paper (TNP) sold like hottest cakes as, in the words of Balji, “football and sex were the two-trick ponies”.

RELEGATED FROM MALAYSIAN LEAGUE

But when Sivaji became the Lions coach from May 1992 to December 1993, taking over abruptly from Czech Milous Kvacek, the unbelievable happened as the Lions sensationally dipped towards relegation in the Malaysian League. Commendably, the Football Association of Singapore (FAS) gave him the backing and the resources to fire the team back towards promotion.

And, with the fire-brand general manager Patrick Ang at the leadership helm for the first time, die-hard football romantics can recall how Fandi Ahmad, Abbas Saad, Alistair Edwards, Jang Jung and Sundramoorthy were all pieced together in 1993 as the Lions assembled the “Dream Team” to secure promotion. Not only did they achieve promotion, they also made it to the finals of the Malaysia Cup that year.

Sivaji recalled in an earlier interview with website Junpiter Futbol: “That was a difficult period for me (after the 1993 loss to Kedah 2-0 in the Malaysia Cup final). I would have lost it, gone into depression if not because of my family and friends’ support. The media was harsh and I almost did not dare to step out of the house. There would be news articles on me almost every day! Singapore was actually winning games but I think the fans were expecting us to win by bigger margin instead. I learned a lot of bitter lessons.”

Balji, with 40 years in five different newsrooms at the Singapore Press Holdings’ Malay Mail, New Nation, The Straits Times and The New Paper, and finally TODAY newspaper (the morning daily Mediacorp published from 2001 to 2017), recollects that when he was given the editorship of The New Paper in the early 1990s, he knew there would be a “major, major (sic) conflict of interest with my younger brother as the national coach” and he approached his chief editor, Cheong Yip Seng, for an editorial alternative.

Cheong, then Editor-in-Chief of Singapore Press Holdings, told Balji: “I trust you completely”. Yet Balji, who took a back-seat when it came to Malaysia Cup coverage, confessed: “I wanted to be whiter than white and told the sports reporters to go ahead and write candidly and criticise the poor-performing Lions…and The New Paper literally went to town with the successive mediocre results of the Lions”.

Months later when Sivaji was replaced by Australian Ken Worden, Balji, for the first time, confessed that he wrote a passionate handwritten letter to his younger brother to “apologise for the critical coverage of The New Paper”.

And when he decided to do his debut book late last year, he wanted to reproduce the letter. But Sivaji, then on a prolonged overseas stint, said it was tucked away in the midst of shifting multiple homes. Balji said: “He clearly showed there were pangs of heartfelt pain, even close to three decades later, and I, too, was very emotional, too, but I wanted to record the football chapters.”

With a very heavy heart, after much poignant after-thoughts, Balji pulled off the chapter on Sivaji and the Lions despite researching a lot on the football-fever from the 1990s. He admits: “It still pains me terribly as I look back as I was caught in an emotional web between my editorial work and sibling-love for my only brother. Much as this triggers my conscience now and evoked me to reluctantly pull off an important chapter from the book, I know I will carry this pain for the rest of my life.”

Sivaji, perhaps one of the most pragmatic coaches I ever met, says: “I never expected my brother, the editor of TNP to tell his staff to go easy on me because I was family. He had to do his job and I am proud that he did not interfere with his colleagues’ work (which he reiterated at the Book Launch).

Knocked blue-and-black by the adverse media publicity, Sivaji bravely picked up the pieces from what he described as the “most challenging sporting years of my life” (although he won the SEA (South-east Asia) Games bronze-medal in 1993) and continued his love-affair with the world’s No 1 sport, returning to the FAS as the last home-grown Technical Director from 2004 to 2007.

He was later elevated to be a FIFA Coaching Instructor and member of the AFC’s Elite Panel on Coaching. Today, he serves as Technical Director at Myanmar professional club Hartharwady United FC for the fourth-year running.

Impassively, he flew in from Yangon (formerly known as Rangoon, the largest city in Myanmar) for the book launch on June 14 and, before a capacity crowd at the Huggs-Epigram Coffee Bookshop in Maxwell Road, recounted the extraordinary brotherly Balji-Sivaji encounter “without fear or favour as it was a very big learning curve in both our lives as we held respective high-profile positions, he as a leading football-tabloid editor and I as the Lions coach”.

WEDDING CONFESSION

Nostalgically, Sivaji also recalled, four decades ago, when he first met his future nurse-wife, Susheela, in the presence of family elders he sought a moment to speak privately to her. And the endearing question: How does a man tell the woman that he is engaged to that while he will care for her for the rest of his life, his first love and duty is to football?

Like a true-blue sportsman of Raffles Institution heritage, while Sivaji promised to love and to care for Susheela, he revealed, almost like a little script from a Kollywood movie, that his “first love was football and that his career in the sport might take him often out of the country”.

Susheela was close to speechless. She thought that it was an odd thing to say as football at that time was not an industry in Singapore where one could make a living. But she believed in Sivaji.

Many years after his marriage that produced two sparkly daughters, who now call Australia home, Sivaji has gone from a Naval Base-starring national team hopeful to coaching the Lions for two years before ultimately becoming a vivid international FIFA-AFC instructor.

Sivaji seriously has no regrets. He looks back at his teenage years, flirting with what Pele called the “Beautiful Game”, at the British Naval Base and that’s where he saw Her Majesty’s Armed Forces first play the game of football. Quickly enthralled by the sport, he took to the game like fish to water. As an energetic teenager, he first broke with Burnley United. Like any other youngster, he grew up dreaming of playing for the Lions, never imaging he’d be the national coach.

EYESIGHT HANDICAP

Like a bubbly football nomad, he moved to other clubs such as Singapore Armed Forces (SAFSA), Sembawang and Singapore Indians (in the Bardhan Cup). But his worsening eyesight prevented him from continuing to play at higher competitive levels. “I think it is important that a man admits when he can go no further,” says the bespectacled balding coach. “I couldn’t achieve my dream of playing for our national team, so I thought that maybe I could help the game by writing about it.”

Remarkably, just as his writing-talented father, Poravankara Narayanan Nair, was a poet, actor and trade unionist rolled into one, Sivaji declined an opportunity to join the newspaper business so that he could pursue his football.

It took several stops and quite a few years as he crawled from the coaching grassroots before he was given the blinding job Head Coach of Singapore. He didn’t make it as a player but as a coach, Sivaji achieved his ultimate sporting dream. Unfortunately, with relegation to the second-tier of the Malaysian League and the 1993 side that he coached fell to Kedah 2-0 in the prestigious Malaysia Cup final.

He found himself under rattling attack from all quarters following the loss, not withstanding his elder brother being a leading editor of the best-selling football-based tabloid, with an extraordinary circulation of over 100,000 – a regional newspaper record of sorts.

After his national coach stint, Sivaji accepted an offer from veteran football boss Richard Woon to coach little-known Tiong Bahru in the-then National Football League (NFL). He later learnt higher-end coaching ropes in Sweden and Germany and continued coaching Tiong Bahru on his return. He was soon named FAS Technical Director until the itch to get back to front-line coaching landed him the Head Coach job at the Bishan-based Home United FC, one of the iconic S-League clubs.

“I’ve been through a lot, you could call it the footballing ‘blood, sweat and tears’,” Sivaji says. “I feel blessed. I have all this knowledge and experience inside my head that I would love to share for many years to come, until my legs finally give way one day. But I’m ready to call it a day when the right time comes.”

And as a final question for what many think is a trophy-less coach, Sivaji says his “biggest achievement in coaching” was the Myanmar FA Cup win in his maiden year coaching overseas with Okkthar United in 2010.

He explains: “I take pride as that is only trophy which I have won as a coach and especially with a young team with no big names. I’m extremely proud of it. The second one has to be the time when I was with star-less S-League club Balestier Central United, in 1999, where we reached the semi-final of the Singapore Cup.”

He holds his head high, too, that he was part of the AFC Asian Cup in Australia 2015 and United Arab Emirates (UAE) 2019 in the TSG (Technical Study Group) which produced the official Technical Report and selected the winners of the competition’s awards. The AFC Asian Cup Technical Report is produced by coaches for coaches, but it is also a publication which has traditionally been of interest to officials, media and fans.

He says: “The finalised report serves not only as a historical record of the competition but also as a detailed technical and tactical analysis, which focus on the performances of the 24 teams and identifies the latest trends in Asian international football. The AFC Asian Cup is a milestone in Asian international football, and the lessons learned from it will have an influence on the further development of the game across the continent.”

For Sivaji and Balji, probably a rarest “first” in the world of two distinguished brothers caught in an awkward football tangle of the highest levels, they know they professionally carried out their respective duties, without fear or favour in any family-way.

And even 27 years later, both candidly admit how they cannot move away from unforgettable family memories and, rather inevitably, still harbour the enduring pain of accidental double-crossings. – By SURESH NAIR.

Suresh Nair is a Singapore-based journalist who knows the star-spangled brothers Balji and Sivaji, who have raised a generation of journalists and footballers respectively and their behind-the-scenes unpublished recounts hold very deep lessons for family and friends.