How big a threat is genetic doping to clean competition in sport?

How big a threat is genetic doping to clean competition in sport?

“It’s a bit like sea serpent,” mythologised, potentially capable of causing serious harm, “but not so present”, said Martial Saugy, former director of the Swiss Laboratory for Doping Analyses.

The lab is in Lausanne, near the headquarters of the International Olympic Committee, which put Saugy on the frontline of efforts to purge drug cheats from globalsport.

In an interview with AFP ahead of the August 5 start of the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, Saugy said anti-doping labs had to keep pace with new methods developed by doping cheats that multiple scandals involving Russia have proved are still a major threat.

But he cautioned against putting too much focus on the still undetermined threat of genetic doping, when other dangers — like micro-doses — are far more pressing.

– Looking for ‘indicators’ –

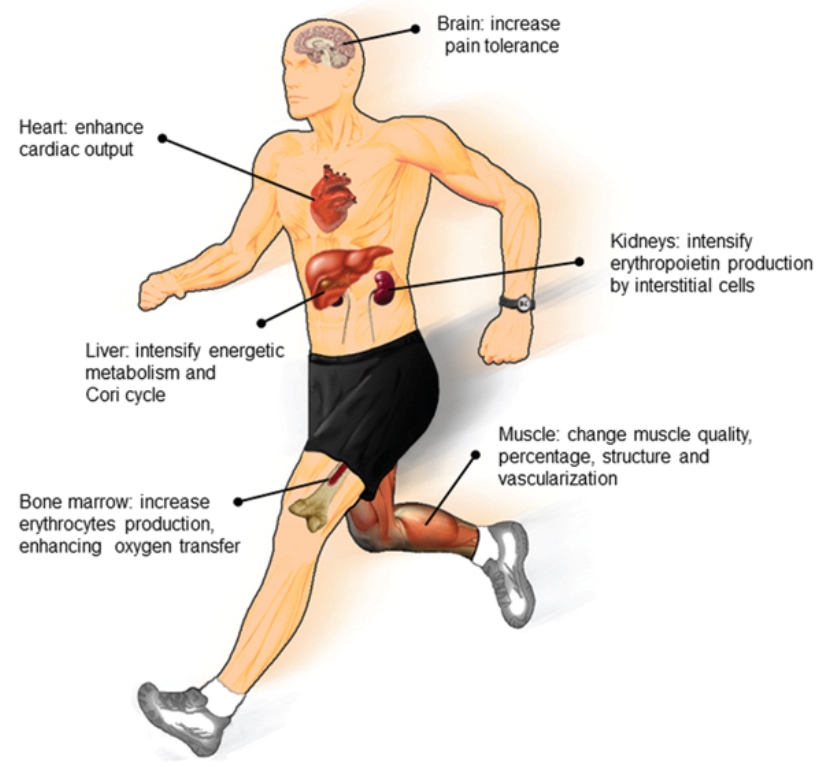

Doctors have for years been experimenting with ways to inject synthetic genes into patients, altering an individual’s genome to enhance muscle recovery or stem muscle deterioration, among other benefits.

Should such treatments be taken up by athletes, anti-doping efforts could be set back years.

“We’ve been talking about it since the creation of the World Anti-Doping Agency in 1999,” Saugy said, adding that the goal for labs is to find a way to detect “the indicators of genetic doping.”

But he noted that since the world’s best doctors are struggling to use the technology to treat sick children, athletes and trainers seeking to cheat with genetic doping are inevitably facing similar difficulties.

“We need to put things in perspective. Genetic therapy in the medical domaine has difficulty getting its place because it’s very complicated,” he said.

Asked if there was a testing system for genetic doping in place for Rio, Saugy, who stepped down from the Lausanne lab last month, said: “there may well be tests but I’m not sure of their relevance.”

– The biggest threat –

“The biggest problem at the moment are microdoses,” Saugy said, when asked about the worst threat to fair play.

Dopers have increasingly realised that tiny doses of steroids or the oxygen capacity booster EPO can be very effective and extremely hard to detect.

Saugy noted that Tour de France 2006 winner and former Lance Armstrong teammate Floyd Landis cheated with a steroid “that is still very present”.

Landis “made an error in usage. Without that error, we wouldn’t have seen anything,” he explained.

The use of biological passports “helps enormously,” said the doctor, who now heads the Center for Research and Expertise in anti-Doping sciences at the University of Lausanne.

“This is one of my main principles: you need to work with the right sample from the right athlete taken at the right time,” he said.

– Changing the system –

Overall, Saugy endorsed the notion that the entire global anti-doping infrastructure needed a shake-up.

In too many cases, private labs motivated by profit are accredited to conduct tests by sport federations, which are sometimes motivated by the desire to see their star athletes have clean records.

Making sure that WADA has the authority and willingness to withdraw accreditation for labs whenever problems occur is crucial to cleaning up the system, Saugy argued.

IOC executives have pushed for a major anti-doping overhaul and have floated the idea of WADA taking over the entire system, removing authority from national sport federations which can be corrupted, as notably happened in Russia and Kenya.

IOC executives last month called for a special summit on doping to be held next year, where enhancing WADA’s authority will be discussed. – Agence France-Presse